It would be really nice to be able to think about reading without thinking about all the ways reading is hard right now. This is, to be clear, not a real problem. It doesn’t even appear in tiny font on the very bottom of the universe’s list of current problems. But if you’re a reader, it feels weird to not be reading, and just about every reader I talk to lately has some version of this complaint. Time is fake. Our attention spans are shattered. What even are books?

I want to push back on this feeling. I want to turn pages, rapt. I want to find ways we can all still fall into books, if and when we have the time and even the faintest inclination to do so. And I keep wondering if, despite my wariness of them, some reading goals might help.

Here’s the entirely undeveloped theory from which I’ve been working: There are goal readers and there are random readers the way there are, among writers, so-called pantsers and plotters. If you are unfamiliar with this slightly awkward terminology, “pantsers” are the fly-by-the-seat-of-their-pants writers, who figure out where they’re going as they’re getting there. Plotters make outlines and plans and know the whole story before they start writing.

Perhaps in readers this manifests as those of us who set reading goals and those of us who scoff at the notion. (I do not have clever terms for these categories; feel free to make up your own.) These goals take all kinds of forms: a simple number of books read; a range of genres; alternating new books and old; clearing out the TBR pile before adding anything new to it; reading authors from different countries and backgrounds. Sometimes goals take the form of the nefarious Goodreads Challenge, a clever bit of marketing on Goodreads’ part that ensures that whenever a user talks about the number of books they want to read in a year, they do it by invoking Goodreads’ name.

I have always been more free-range reader than goal-setter. Goals? Plans? A reading schedule? Impossible: How do you schedule moods? If you’re the kind of person who turns to books—consciously or not—for a feeling, an atmosphere, for an adventure you didn’t know you wanted to go on, then it seems impossible to plan these things. You don’t know until you read the first few pages if a book is the right one for the moment. If you’re a reader like this, you can’t simply decide that you’re going to read War and Peace next. You have to be in the War and Peace mood. It’s hard to read War and Peace when your brain and your heart are crying for Legendborn.

But I do keep a reading spreadsheet, so it’s not entirely chaos over here. I track what I’ve started reading, when I finish it, and basic info about each book that is meant to show me at a glance whether I’m reading a wide range of books, or things that are too similar. “Too similar” can mean anything: too many new books, too many books by straight white men, too many YA novels and not enough nonfiction, you name it.

A spreadsheet like this will not allow a reader to lie to themself. You can, to offer just one example, feel like you’re a person who reads widely and diversely, and then your spreadsheet will point out that last year you read a lot of Le Guin, The Expanse, The Wicked & the Divine, and all the Old Kingdom books, which adds up to a lot of white authors. Feelings, as many wise friends have reminded me, aren’t facts. The reader I feel like I am is not the reader I was last year. There is absolutely nothing wrong with all of these books—there is a lot very, very right with them—but I don’t want to get in ruts. I don’t want to read mostly white authors, or mostly male authors; I want to read way beyond that.

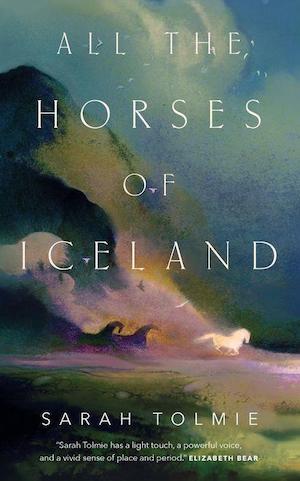

Buy the Book

All the Horses of Iceland

And that’s where goals can be useful: for keeping yourself on the tracks you want to be on. That track can be as simple as just reading books by women for a year. Or maybe it’s alternating classics with brand-new books, and filling out any gaps in your reading education (for several years, I ran a classics book group for exactly this purpose). You can also get really specific, and make a list of authors or genres or perspectives you want to read more of. Book Riot’s annual Read Harder challenge offers a detailed list of “tasks” for each year; for 2022 that includes “Read a book in any genre by a POC that’s about joy and not trauma” and “Read a queer retelling of a classic of the canon, fairytale, folklore, or myth,” two excellent suggestions.

I’ve always squirmed away from these challenges and goals, which can be chalked up—at least in part—to simple stubbornness and/or a lifetime wariness of goals in general. (If you are also a person who sets goals too high and then gets frustrated when you don’t reach them, hey! I feel you.) Reading goals and challenges can tiptoe up to productivity culture, which gets real toxic real fast; reading shouldn’t be about how many books you read, or how fast you read them, or how to create more content about them. They can turn art into tickyboxes, feeling more like a to-do list than a way to thoughtfully engage with perspectives and voices unlike our own. And setting reading goals can feel like time spent planning instead of doing: Why sit down and make a list of what you want to read when you could just, you know … read it?

Because you run into aggravating book moods, for one reason. And because you might wind up with a more homogenous reading list than you intended or expected, for another.

I’m still not fully sold on goals that are just a number of books (though I will certainly consider any good arguments). But when you have a list of specific goals—or even just ideas, thoughts about what you want to explore—it can be a way to narrow down the endless possibilities a reader faces. I’m really not good at giving up the power of choice. I can never leave things up to a roll of the dice, or pulling something at random from the shelf. But if I decide that this year, I want to read a science fiction novel in translation, my first Samuel Delany and Joanna Russ books, a horror novel that even a wimp can stomach, and a book about the craft of writing that’s not by a white man, then I’ve translated nebulous desires into something simpler: a decision about where my reading time goes. And maybe a bit of direction as to what to read first.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.